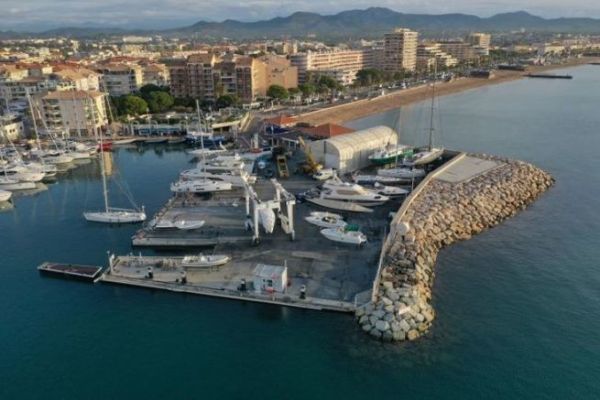

Direct management imposed in a tense climate

The decision by SPL Ports de Fréjus not to renew the public service delegation for the operation of the shipyard, effective August 2, 2025, marks an abrupt turning point in the management of this infrastructure. The shipyard, hitherto entrusted to a private operator, will be temporarily taken over directly, with a workforce reduced to four from the current twenty-five.

This decision, justified by the SPL as a project to modernize the dykes ahead of a new call for tenders for a five-year public service contract, has been strongly contested by the outgoing operator. The latter deplores the lack of consultation, the absence of any credible economic justification, and points to the risks of a hasty dismantling of a production tool that generates 700,000 euros in annual sales.

A strategic tool for the port's competitiveness

The Port-Fréjus shipyard is more than just a logistics center. It provides essential technical services â?" mechanical repairs, painting, refit, renovation â?" which are vital to the quality of the port welcome and to retaining the loyalty of yachtsmen. Its shutdown or functional deterioration could divert a demanding clientele to competing ports in the region, better equipped or more stable in their management.

What's more, the reorganization is taking place without any clarification of the company's ability to maintain service levels, or of the investments required to absorb the organizational shock. For the economic players based around the port, this disarticulation of the technical platform compromises business continuity in the short term.

Uncontrolled legal and social risks

Beyond the economic effects, the transition raises legal questions. The operator is contesting SPL's intention to recover certain equipment it claims to have acquired in 2011. This equipment, essential to the operation of the site, could become the subject of litigation if no compensation is forthcoming. Legal proceedings are envisaged.

On the social front, the drastic downsizing has not yet been accompanied by any compensatory measures or transition plan. This lack of clarity is exacerbating local tensions, especially as the local authority has not yet communicated a precise timetable for the relaunch of the public service contract, or the human and technical resources that will be mobilized in the short term.

The Port-Fréjus case illustrates the growing tensions surrounding the governance of nautical infrastructures. Between ambitions for reorganization and a lack of consultation, the method used raises questions. At a time when the industry is being called upon to structure itself around sustainable models, this operation demonstrates the fragility of local balances and the need for concerted steering to avoid abrupt ruptures. The future call for tenders will have to provide clear guarantees to operators and users alike, in order to restore confidence.

/

/